There Are Better 20’s Fashion Icons Than The Peaky Blinders

The effect Peaky Blinders has had on the vast majority of the UK population is staggering. The highly anticipated Season 6 premiere of the show garnered 3.8 million viewers, but fans were preparing for its comeback far before.

Following the announcement of the season’s release date, suit outfitter Moss Bros reported a 110% rise in searches for flat caps, and searches for three-piece suits rose by 250%. As reported in the Telegraph, John Lewis saw sales of flat caps increase by 83% after the release of the show’s third season, and they have continued to rise a further 25% annually ever since. This popularisation of clothing worn by the 20th-century working class has been titled the ‘Peaky Blinders effect’.

With impressive tailoring mixed in with hyper-masculine action, blood and gore, it’s no surprise that many middle-aged men see the Shelbys and want to emulate their style. The whole spiel of ‘British working class’ and ‘it’s authentic’ falls from their lips when they mean they want to cosplay as cut-throat gangsters.

It’s a bit of a phenomenon. Since the show’s first season, numerous articles have been shared across the internet by ‘gentlemen’s’ magazines detailing how to perfect the Peaky Blinders look. The outfits favoured by these fictional gangsters speak to the very real and British post WW1 era, sense of polished suiting and traditional fabrics; tweed coats, three-piece suiting, penny collared shirts, polished boots, pocket watches, and the iconic flat cap, who’s peak has been known to conceal a few razor blades.

While mostly an accurate depiction of style at that time, the Peaky Blinders look is one take on ’20s and ’30s fashion. The Shelby family and co may opt for dark, dingy colours that reflect the dismal Birmingham landscape, but the real people of this era can offer us a more vast and interesting fashion inspiration.

There was a huge shift happening in fashion during the roaring ’20s. The first World War had just ended, women in the UK and USA had finally been granted the right to vote (though there were many caveats), and the US was experiencing prohibition. Despite this, economies started to boom after the gloom of the war years. The Jazz Age brought with it high-octane parties fuelled by ragtime dancing, and speakeasy’s rebelled against the alcohol ban. The Harlem Renaissance, an intellectual and cultural revival of Black music, dance, art, fashion, literature, theatre, politics and scholarship centred in Harlem, Manhattan, New York City, asserted a renewed pride in Black life and identity while rebelling against inequality and discrimination. The cultural scene exploded with the talents of Pablo Picasso, Ella Fitzgerald and Duke Ellington, and iconic cultural works were being created by the likes of Ernest Hemingway, Langston Hughes, and F. Scott Fitzgerald. There was so much life happening, and, as ever, fashion embraced it all.

Costume jewellery, especially fake pearls and jewel pendants, became popular as people searched for attainable luxury. Coco Chanel created the first-ever Little Black Dress, trousers started to become acceptable attire for women, and, while we all struggle to match our handbags to just one aspect of our outfits today, women were matching their gloves, shoes and handbags to their outfit.

For a brief period in the ’20s, hemlines grew shorter than ever before, and stockings and decorative tights became a staple with those daring to show their knees. But no matter the length of the dress, throughout the decade, waistlines sat relatively low on the torso, the aim being to elongate the body’s upper half. The popular flapper style of the ’20s, the most recognisable dress of the time, would hang straight down from the hips to further the illusion of an elongated torso.

In contrast, the ’30s saw hemlines descend back to ankle length, and the waistline returned to its natural place on the body. Dresses would either flare slightly in light pleats from a defined, cinched waistline until they hit the floor or cling to the hips and upper thigh. While the dresses technically covered every inch of the wearer’s skin, the way they hugged the wearer’s frame, defined their waist, and accentuated curves made them relatively revealing for the era.

In a surprising twist, women of the 30s followed a similar trend to those of us in 2022 – knit two pieces. The most desirable attire for the time was not practical as everyday wear as women of this decade primarily worked in service industries; not the best place to be wearing a figure-hugging silk dress. To remedy this, Coco Chanel released a comfortable, jersey-knit two-piece suit as a relaxed option for women’s day wear. This came as a long, loose skirt with a suit jacket that’s more reminiscent of a modern cardigan or sweatshirt than any type of coat. Most importantly, this design brought the idea that women could be comfortable in their clothing, something that hadn’t been thought entirely possible before.

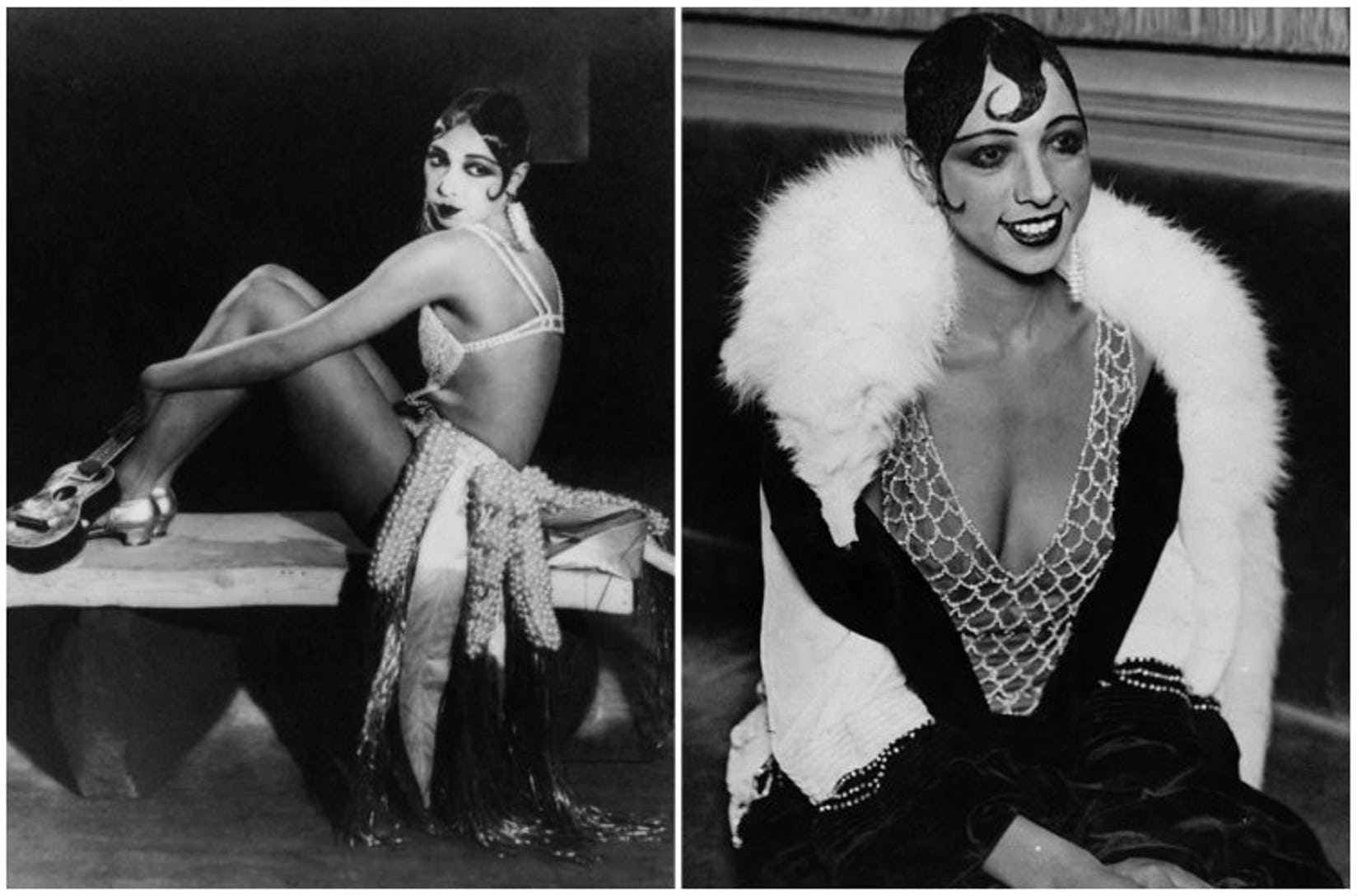

In place of a Peaky Blinder, your real 1920’s style inspiration should be coming from people like Josephine Baker. Not only was Baker a phenomenal dancer in Paris, but she was an activist, an anti-Nazi spy and an absolute fashion icon. Her life needs no embellishments to become TV worthy, unlike the beloved fictional gangsters. She might be best known for performing in a skirt made of 16 bananas strung together with nothing but a string of pearls as a top, a feat in itself, but all of Baker’s on-stage outfits were miles more interesting than the 3-piece suit of a Peaky Blinder.

Baker brought with her the soul and style of the Harlem Renaissance, which gave her an incredibly empowered and modern sense of style. Looking at some of her pictures, you may seriously contemplate whether she had a time machine. She was a hundred years ahead of numerous modern-day trends. She regularly wore and was pictured in slitted maxi skirts with matching crop tops, off the shoulder gowns, and chain mail bralettes, to name a few.

As her fame mirrored the emergence of art deco, Baker’s style was heavily influenced by the movement. When wearing clothes made of actual fabric, the fashionista opted for sleek lines and geometric shapes. Her waist was pulled in, reflecting the preferred ’30s silhouette, and her hair was most commonly seen gelled all the way down, with a sort of fringe glued into a large cowlick on her forehead.

Amid all her flamboyant looks, Baker could also effortlessly pull off monochrome outfits and would add her own flair to simpler ensembles with her more is more attitude towards jewellery. She would pair ropes of pearls with door-knocker earrings and oversized rings, always managing to look glamorous and not at all over-the-top. No Baker look would be complete without an elaborate, sky-high hair accessory boasting a myriad of jewels and feathers. Bakers’ most excessive accessory? Her pet cheetah, Chiquita, who wore a diamond-encrusted collar as she walked along the streets of Paris.

If you ask anyone, especially Josephine Baker, a feather boa-d headdress is a much more exciting headwear than a flat cap; you could probably hide a bigger weapon in there too.

Discover more from GUAP’s Fashion section here

![ZINO VINCI’S ‘FILTHY & DISGUSTING’EP BRINGS YOU TO THE CORE OF THE ARTIST [@ZinoVinci]](https://guap.co/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Zino-4.jpg)