Simon Wheatley on The Limitless Evolution of Subcultures

In the lead up to Abbey Road Studios’ newly announced Music Photography Awards–a first of it’s kind–GUAP caught up with Simon Wheatley, the groundbreaking social archivist and world renowned grime scene photographer who is joining as a guest judge for the Hennessy partnership and ‘Championing Scenes’ award at the upcoming event in May, shining the spotlight on photographers reporting music subcultures around the world.

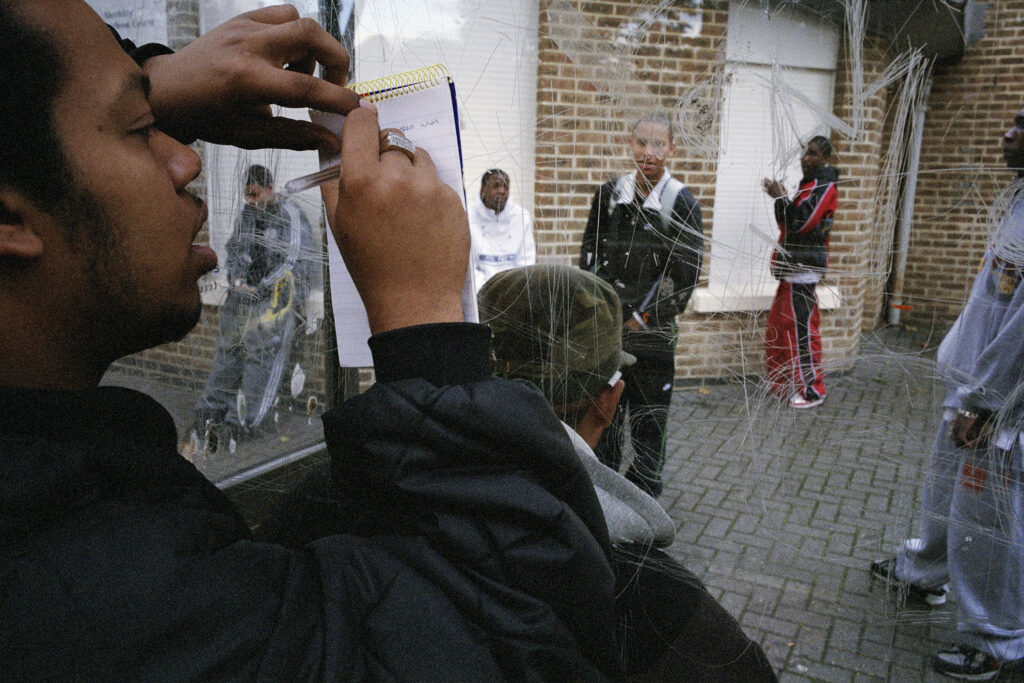

Covering a myriad of impactful moments throughout his career we deliberate on grime’s presence in contemporary scenes, the growth of social medias and the subsequent influence on sub-cultures. Wheatley is without a doubt a verifiable veteran in the ever-changing creative fields across the UK today, capturing the squidbelly of London’s grime scene, through visual materials from photography to film. The images taken for the project, privy to social and industrial changes over time, present a blend of London’s landscapes and portraits featuring artists in their struggle, an unfiltered lens of estates and life ‘on road’.

As we continue to contend with unrelenting shifts in the world around us the lasting power and presence of sub-cultures on today’s musical stage is far more complicated than the Limewire and MSN days. On the cusp of another decade under ‘the Tory’s obsession with austerity’ as Wheatley puts it, grime quickly became one of the most significant genres to be born out of the UK. “Original grime will always be original grime. But evolution is the nature of things, and human history shows that resurgences are always part of us too.” adds Wheatley.

Speaking on why he was drawn to undertake the quest he observes “I was largely driven by an urge to explore the social realities of a confrontational sound”. Living in London’s infamous basin, Limehouse, Wheatley decided it was about time someone picked up a lens and started to capture the fading authenticities which were integral to the emerging underground scenes, namely through London’s council estates and grime music in the 2000’s–leading to his first published book, Don’t Call Me Urban!, in 2010.

The multimedia visionary is now working towards two new literary projects, one being Lost Dreams, which he describes to be more like a fanzine and the second is a wider anthology concerning the evolution of grime as a genre. For the latter, the E14-native has combed through his whole catalogue of work over the decades. Delving into how grime’s identity has been diminished over the decade, with fundamental landmarks of the genre slowly disappearing or already gone. Things like pirate radio and cardinal estates being demolished making the documentation of such scenes all the more vital.

From first putting a camera to his eye during his last year of university in Brazil, to becoming a lone wolf at his apex in the documentation of one of the most iconic subcultures in music today. Wheatley’s experiences spanning over his career chalk up to explain exactly why he is an ideal judge for the upcoming awards show, a true herold for burgeoning photographers and creators alike.

Catch the full interview below and reignite your love for all things grimey: 140bpm tempos, unforgiving bars, iconic estates and see what’s next for music subcultures in this current terrain.

GUAP: What made you decide to step into the behind-the-scenes of such a pivotal genre that is grime?

SW: I was already deep into photographing London’s council estates when grime emerged around the same time as I came to live in Limehouse, E14. Who knew that the genre would become so pivotal? Probably no one, even though grime did seem something of a mass movement in East London and in retrospect the enthusiasm around me might have given the impression that something was going on. But I was largely driven by an urge to explore the social realities of a confrontational sound.

“I was largely driven by an urge to explore the social realities of a confrontational sound.”

Grime stretches back beyond the early 2000s, and people still talk about albums like Dizzee’s Boy in Da Corner as the ‘golden era’ in Grime Music, which is around the time you released your first book Don’t Call Me Urban! in 2010. With your latest book will you be talking about Grime in the present or past tense?

Well, there are two books that I’ve been working on over the past couple of years. Lost Dreams is more of a fanzine, that will pay some homage to the youth club culture which was so important in early grime. And I have been editing through my entire grime archive and also the work I’ve done since Don’t Call Me Urban! for a wider book about grime, which will be much bigger than what was published in 2010. This will also feature some video stills as I’ve been almost equally as active as a film maker since then. Lost Dreams is very much in the past tense of course, but it does have contemporary relevance in provoking a debate about the absence of youth clubs after this decade of Tory obsession with ‘austerity’. The wider grime anthology will also feature many pictures from the early days that were not published in DCMU!, and while at a glance I would say that we are talking about the past tense, I sometimes find myself around people I first met almost twenty years ago and photographs I make of them in 2022 are also in the mix for the edit. Is grime the past or the present? The music has lived on but in terms of the visual culture I think that to photograph grime you had to have done so in the first decade of this century – that’s when grime happened. I suppose it’s like saying that you could photograph a punk band in the 1980s but to really photograph punk you had to have been there in the 1970s. Grime was about the youth clubs and pirate radio and these were over by the time of grime’s resurgence. And several of the estates that were so iconic to grime’s visual identity had also been either demolished or refurbished.

“‘Lost Dreams’ is very much in the past tense of course, but it does have contemporary relevance in provoking a debate about the absence of youth clubs after this decade of Tory obsession with ‘austerity’.”

What was the process behind deciding on which artists to spotlight in your book?

My journey has always been very organic and those relevant to grime’s history who I’ve met along the way are obviously there, but a photograph also has to be good enough on aesthetic grounds to be included. Like DCMU!, the grime anthology will also feature many pictures of unknowns – it’s a focus on the culture more than those who became its celebrities – although I will also be including several of the contact sheets of the shoots I did for Rewind magazine and those were of the grime stars. There is no process as such, other than to make sense of my fortunate experience and provide some definitive tribute to a genre that became so monumental.

When you talk about the evolution of Grime what kind of timeline do you look at? Are there pivotal musical influences you touch on which date back to before grime?

I was primarily a social documentary photographer who liked music, and I just stumbled into grime. I do remember garage being very popular in the years leading up to its emergence and there will be a portrait of Miss Dynamite in the grime anthology as a testament to that. Of course I’m aware of the other genres that influenced grime – but all I have of that beyond my interest in Caribbean musical culture are pictures of American rappers on the bedroom walls of London’s grime generation.

Could you briefly break down to us your process when working on a photography project? Is it thoroughly planned or left to snowball naturally?

Nothing is planned. I tend to be very passionate and just follow something and go deeply into it. That’s the beauty of creative life.

You will be a guest judge at Abbey Road Studios Music Photography Awards in May, picking the winner of the Hennessy “Championing Scenes” category. Is there a particular subculture at the moment that you’d like to see amplified? And if so, how do you see these being documented through photography?

On a very fundamental level, I do wonder about the existence of subcultures these days. Has social media made us too aware of everything? In the past, subcultures were almost secretive – certainly in the phase of inception. Grime was heard via illegal radio stations, it wasn’t really seen – videos were not common like they are today. Unless you got your picture into Rewind Magazine your face wasn’t commonly known. Times change however, situations evolve, and I’m curious to see how the concept of subculture has adapted to new realities. I like to see good photography, that’s very important for me. It’s not so much whether I want to see a particular subculture amplified but about the sensitivity and intelligence that goes into portraying it.

“On a very fundamental level, I do wonder about the existence of subcultures these days. Has social media made us too aware of everything?”

Your photography made me think about formats and how CDs and tapes were very good for certain kinds of music, like grime. But do you believe that the streaming world and grime world could ever line up?

Vinyl was also a huge part of grime. Streaming has to be too.

What makes a good scene photographer? What takes their work to the next level?

A ‘scene’ can be very limiting. Someone who goes beyond it has a chance of progressing.

Where do you feel like grime is at in terms of mainstream presence in music now? And do you think that will change in the near future with the resurgence of garage-like breakbeats which were a strong foundation in grime?

Grime progressed to become the mainstream, with its resurgence around 2014. We don’t need to list the names to recognise that, the people who came through the genre. And grime paved the way for other genres emerging from the same social constituency to reach the same heights. I know some grime fans despair when someone they have revered tries something else, something beyond 140bpm perhaps, but I have never felt that an artist has to stay with whatever he did in his youth. I would say that it goes against what the essence of art is all about. Artists are meant to evolve. Look at Miles Davis. What he was doing in the 1940s and then thirty years later was remarkably different. Am I digressing from your question? Maybe, but you know what I mean. Maybe because grime was so pivotal in terms of putting the UK on the map in hip hop culture, emerging from that great shadow across the pond, that people feel it must always be true to its foundations. And yes in a way it should, that distinction should be recognised in the annals of musical history. Original grime will always be original grime. But evolution is the nature of things, and human history shows that resurgences are always part of us too.

“Artists are meant to evolve. Look at Miles Davis. What he was doing in the 1940s and then thirty years later was remarkably different.”

How do you feel this new era in grime will reflect previous eras?

Grime was about a social condition, it was the voice of an underclass. What I’ve found interesting is the way that grime has somewhat returned to the margins with the emergence of drill. On another level of observation, one can argue that grime became drill. Drill is also the voice of an underclass, as the name ‘grime’ implied. That underclass continues to exist.

![ZINO VINCI’S ‘FILTHY & DISGUSTING’EP BRINGS YOU TO THE CORE OF THE ARTIST [@ZinoVinci]](https://guap.co/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Zino-4.jpg)