Luxury fashion conglomerates: the death of fashion innovation?

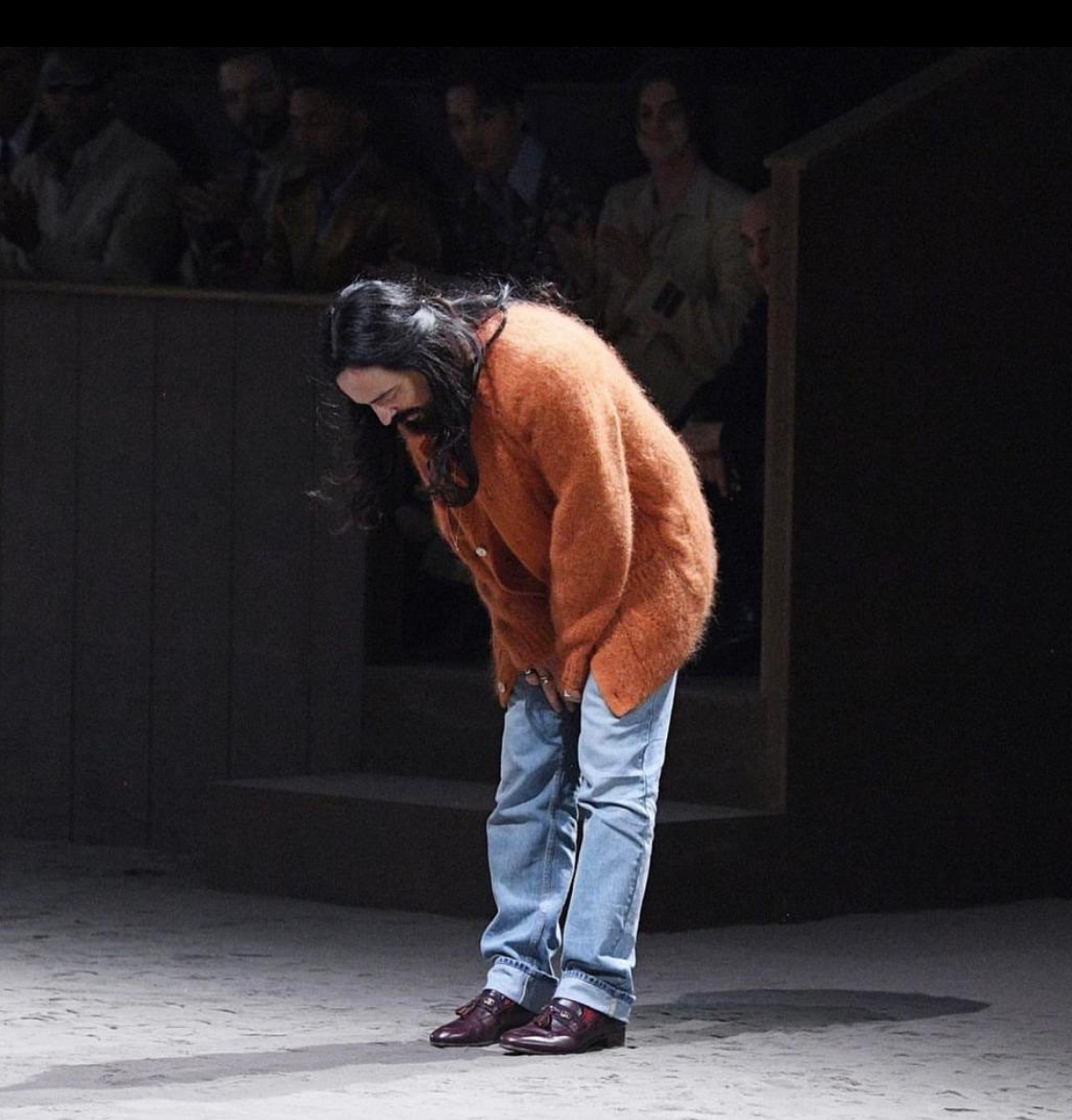

Just four weeks after Gucci’s creative director Alessandro Michele’s abrupt exit, the Kering-owned brand announced their return to Milan men’s fashion week for the first time in three years. This is noteworthy as Michele’s signature of blurring the lines between menswear and womenswear had made Gucci move to a single co-ed show instead of separate mens and womens.

This move back to the antiquated tradition of separated mens’ and womens’ therefore displays a harsh dismissal of his legacy. Between the rumours, PR statements and Instagram captions it is clear that this was not a mutual decision. Moreover, if Michele’s craftsmanship, creative innovation and cultural impact was not enough to save him; what does that mean for other leaders of fashion innovation?

Since the 1980s, there have been three major luxury fashion conglomerates: LVMH, Kering and Richemont. Between their three holding companies, Bernard “the wolf in cashmere” Arnault (LVMH), François Pinault (Kering) and Johann Rupert (Richemont) own 128 luxury brands. LVMH is way ahead of the pack, which is unsurprising as they are the pioneer of the luxury conglomerate model, and their CEO has a notoriously aggressive approach to business.

Whether you believe that this model is just an example of brands outsourcing commercial worries to the most qualified, or that all fashion brands should be run independently, luxury fashion has proved to be big business. Arnault is the richest person in the world. But what does this mean for emerging, innovation focused luxury brands?

Hanifa gained global notability after their 2020 virtual fashion show went viral. This led to not only growth in brand awareness but tangible and sustained commercial results. Their April 2021 six piece capsule collection generated $100,000 in sales on its first day. Despite this success, founder Anifa Mvuemba has decided to continue bootstrapping her business, operating without external investors. Mvuemba used her tax refund as seed money, a CFDA grant of $50,000 and reinvested profits to grow her brand sustainably. Hanifa’s success, along with that of other fast emerging, independent brands such as Coperni and Jacquemus, shows that craftsmanship, cultural capital and commercial success can be achieved outside of a fashion conglomerate.

Independent brands such as Giorgio Armani and Ferragamo consistently go head to head with luxury conglomerates and have stood the test of time. Unfortunately, luxury conglomerates are not the only hurdle for smaller labels. A key issue post Covid has been the extraordinary increase in cost of fashion production, from importing costs, labour costs to the price of fabric. The increased cost of living also means that consumers have less disposable income. This means that fast fashion brands that steal designs from smaller independent labels, that can foot the production costs and sell at a much lower price, are often where consumers turn to instead. This cocktail of blockades – luxury-conglomerates with a large percentage of market share, equally large fast fashion brands and the global cost of living crisis; mean it is understandable that emerging brands are struggling. In the conversation about innovation this is a huge concern as emerging independent brands tend to be the most innovation focused designers in the fashion industry.

So, back to the question: are luxury conglomerates the death of innovation focused fashion? The recent Loewe, Coperni and Jacquemus shows would suggest that brands both within and outside of these conglomerates are still flourishing creatively. However, the sudden exit of Alessandro Michele at Gucci, the staleness of fashion week presentations and the closure of culturally significant brands would agree. For example, in 2019 fashion protege Zac Posen was forced to close his company, citing struggling to find “the right partner” over a decade as the reason why. In theory, amazing talent, competing in CFDA/Vogue Fashion Fund contests and gaining the seal of approval from American Vogue and Anna Wintour would be enough. But this is no longer the case in the current conglomerate-dominant world of fashion today. It’s increasingly difficult to compete with your mid-sized luxury counterpart when they’re conglomerate-owned.

Of course, prioritising profits and money is as essential in business as prioritising creativity is in fashion. However, art is essential to life, and what is fashion if not wearable art? If the business side of fashion engulfs the art side what will we be left with? It seems we can only wait and see.

Read more GUAP fashion content here.

![ZINO VINCI’S ‘FILTHY & DISGUSTING’EP BRINGS YOU TO THE CORE OF THE ARTIST [@ZinoVinci]](https://guap.co/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Zino-4.jpg)

1 Comment

[…] and beauty trends of the season, they also have a major economic impact on each city. Fashion conglomerates have proven that luxury fashion can be big business, so these weeks also act as key networking […]

Comments are closed.