Why it’s crucial the UK pays attention to the #StopAsianHate movement

Asian racism is intricately woven into our everyday lives yet in order to become aware and understand this reality, we need to begin to change our customary habits to relinquish these hierarchical norms which place POC at the base.

Contribution by Jessica Rogers.

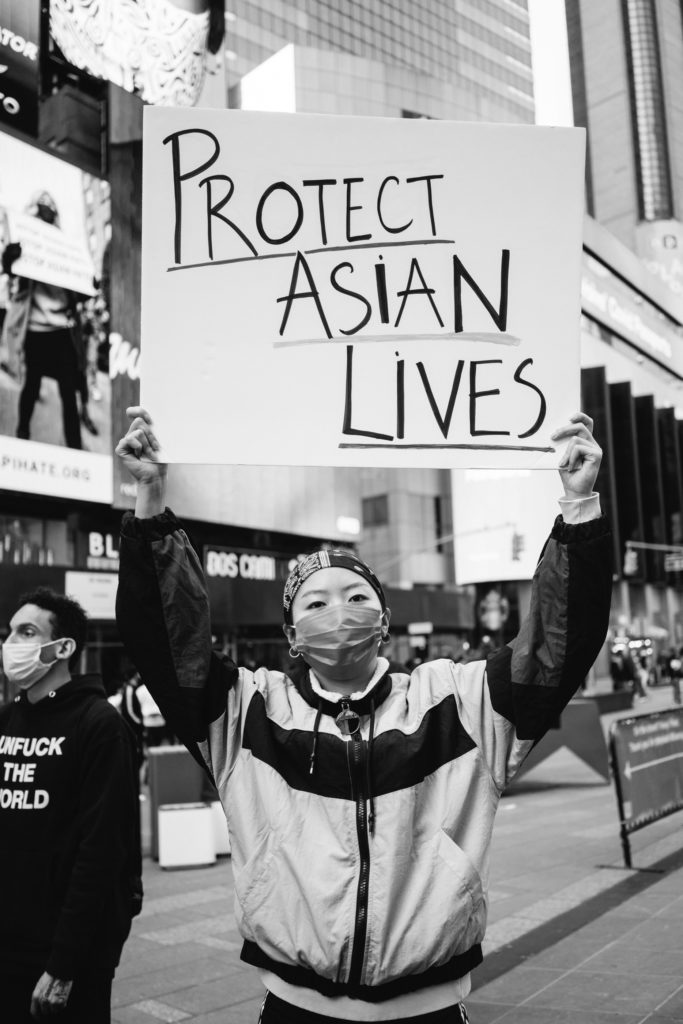

Over the last month worldwide support has been rallied for the #StopAsianHate movement after a series of events sent shockwaves through the globe. US citizens took to the streets to demand justice for victims of racially charged hate crimes against Asians which have transpired since the onset of Covid-19. While the movement is gaining pace in the US, like the BLM movement, there is an urgent need to recognise that the issue is not confined within the parameters of US borders but is very much entrenched here in the UK too. Now the conversation has been sparked, it is fundamental that we seize this opportunity to gain an understanding of what the face of racism towards Asians looks like in our country and why it’s been long overlooked.

Coverage of hate crimes against Asians in mainstream media is minimal, but with a surge in racist fuelled attacks targeted at Asians across the world and footage of the incidents being flooded all over social media, it’s left media outlets little choice but to acknowledge the issue. UK police data indicates a 300% increase in hate crimes towards people of East and Southeast Asian (ESEA) descent in the first quarter of 2020 compared to the same period in 2018 and 2019. Last year, numerous incidents were reported of ESEAs in the UK being assaulted, having their jaw broken, having their clothes torn off, being spat on and having their restaurants vandalised. While these attacks left no room for ambiguous motivations, what has been and still is most prevalent in the UK’s society is the manifestation of subtle, covert, and institutional forms of racism that fails to be covered by mainstream media.

Trump was condemned for preaching xenophobic and inflammatory rhetoric – ‘the Chinese virus’, ‘Wuhan virus’, and ‘Kung flu – to incite association with and blame ESEAs for the virus. Yet at the same time, the British media has similarly perpetuated this harmful social stigma by routinely using images of Asians to report on coronavirus, despite the individuals pictured being completely irrelevant to the story. Over 33% of images used to report Covid-19 were of East Asians, resulting in the same harmful narrative that Trump’s derogatory rhetoric did – that the face of coronavirus is Asian. While Trump’s racist comments were easy to decipher, racism in the UK presents itself as an undercurrent that is harder to distinguish but is just as pervasive.

On further consideration, the acts of hate that have been playing out across the country have been instigated by a narrative formulated by a journalism industry that is 94% white and a government that is 90% white. Underrepresentation of minorities is a danger to equality in all forms, but what’s even more concerning is our very own government’s attitudes and behavior. In October 2020, Parliament held its first-ever debate to discuss the racism experienced by the ESEA community. Not a single Conservative MP or government minister turned up.

During the debate Labour MP Sarah Owen – the first MP of southeast Asian descent – revealed that Tory Ministers had shared coronavirus jokes with caricatures of a person in a Chinese pointy hat, bucked teeth, and slanting eyes. On another occasion, two MPs sat in the same room as her and referred to Chinese people as “those evil bastards”,and said “oh, you know how they look.” It begs the question, how can we rely on a government that does not show up to acknowledge the harm committed to ESEAs and even more so, scapegoats, alienates, and silences them themselves? Rather than protecting Asian communities, their actions are actively providing racists with the justification to unleash their ingrained biases.

Another Tory councilor received backlash after liking a comment on Facebook in relation to the Chinese company Huawei, which read, “You can’t trust these sweet and sour dogs, let alone national security”. His defence to which was ‘it was a satirical comment.

Herein lies another major obstacle as to why racism towards Asians goes unaddressed – enforced stereotypes where Asians are the brunt of the joke and should passively laugh along. The hyper-sexualisation and fetishization of Asian women have long been a big joke; Asian women portrayed as mail-order brides, sex workers, docile, demure, and obedient beings are just a few of the outdated classics. What needs to be acknowledged is that stereotypes that dehumanise Asian women are inextricably linked to the violence they face.

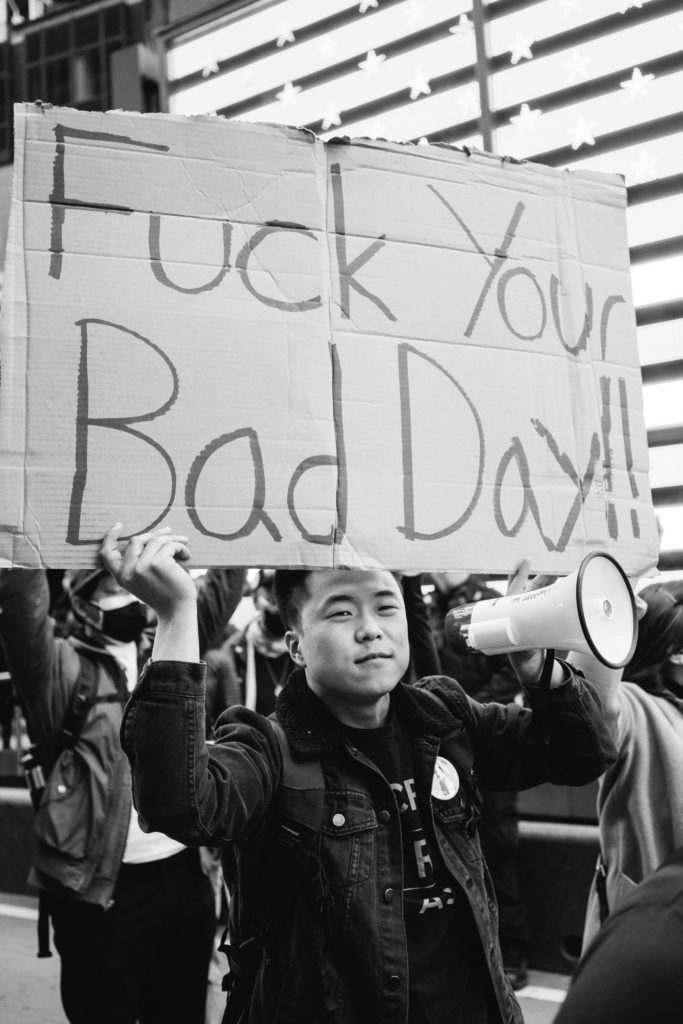

The revelation that the shooter of the Atlanta attacks – where six of eight of the victims were Asian women – suffered from sex addiction and visited spas run by people of Asian descent as he thought they were the safest place to pay for sex, ultimately cements this reality. The judgment that the attack was sexually but not racially motivated by a powerful institution, like the police force, fails to recognise this mutually intertwined relationship. To add insult to injury, the conclusion by the Atlanta Sheriff’s Captain that the attacker had a ‘really bad day’ only works to reinforce that brown lives aren’t valued, terrorists are not white, and that history will continue to repeat itself until these racist perceptions are dismantled.

While the demonisation of Asians in the media is commonplace, positive representation is a rarity. Where are the headlines and prime-time broadcast features which highlight how Filipino nurses have risked their lives more than any other demographic in the UK to fight Covid-19? While the Filipino community makes up 200,000 of the UK population, almost 10% of them work for the NHS. Research carried out by HSJ in May last year revealed that Filipinos were the single largest nationality to die from the virus, making up 22% of nurse deaths. And only the other week New Zealand was celebrated as a feminist force in the press after ‘becoming the first country to legalise paid leave for miscarriages’ when in reality the Philippines passed the same law years ago but failed to be heralded as world leaders in the same respect. It is so imperative that positive contributions of Asian communities in the UK, as well as abroad, are vocalised in order to shift attitudes away from the harmful depictions that currently persist.

Attitudes towards beauty ideals are also in major need of a shift. The eye shape of East Asian natives has long been a feature deemed undesirable, surgery to adopt a more westernised appearance in the region is conventional. However, the rise of the ‘fox trend’ last year once again showed that westerners set the standard for beauty. Kendall Jenner and Bella Hadid underwent surgical procedures to acquire elongated eyes. Naturally what followed suit was a tsunami of Instagram and Tiktok posts of girls pulling their temples outwards to replicate this eye shape. Cultural appropriation of ethnic minorities is rife nowadays; features that people of colour (POC) naturally exhibit too often become ‘trends’ to be replicated by Caucasians through cosmetic surgery and beauty treatments. Big lips, tanned skin, thick bushy eyebrows, elongated eyes – all features that POC have been taunted for, yet once they are adopted by white people, they are idolised and celebrated. While tailoring aesthetics isn’t a malicious act of racism, it needs to be recognised that white people have the privilege to do so as they please, without being subject to discrimination and bullying.

Asian racism is intricately woven into our everyday lives yet in order to become aware and understand this reality, we need to begin to question and accordingly change our customary habits to relinquish these hierarchical norms which place POC at the base. An unequivocal example of this is the reliance on Asian communities to uphold the West’s insatiable demand for fast fashion, an industry notorious for its exploitative and unethical practices. There are around 75 million people working in the garment industry worldwide and the Asia-Pacific is home to around 65 million of these workers.

However, the Boohoo scandal last year revealed the exploitation of Asian bodies is closer to home than we thought. An undercover investigation revealed a factory in Leicester contracted by the popular fast-fashion brand and its subsidiaries – Pretty Little Thing, boohooMan, Miss Pap, and Nasty Gal – was subjecting workers to slave-like conditions and an illegal wage of £3.50 per hour. The majority of employees were women of South-East Asian descent. While shopping doesn’t spring to mind as a political act, on deeper reflection it is inherently politicised. In this day and age when being a Pretty Little Thing ambassador is glorified, fast fashion brands are more deeply embedding the disvalue of Asian people. Not buying from brands that are renowned for exploiting Asian people is an accessible act that can help begin to tackle the institutionally racist world order.

Racism in the UK manifests itself in elusive ways that we must decipher from unambiguous, overt, in-your-face racism. The recent Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities report accepts there’s work to be done to address overt racism but denied that institutional racism persists. So, to even begin to enact change there must be collective effort as a nation to firstly acknowledge that racial injustices occur out of plain sight, white privilege is real and deep-seated biases must be unlearnt. Then it’s vital our government, the media, law enforcement agencies, and corporations are held to account for the role to play in perpetuating anti-Asian sentiment, exploitation, and upholding white supremacy. Our culture, festivities, and food are celebrated, but now we must be celebrated too.

Contribution by Jessica Rogers.

Check out the GUAP Arts & Culture section, to discover new art, film, and creative individuals.

![ZINO VINCI’S ‘FILTHY & DISGUSTING’EP BRINGS YOU TO THE CORE OF THE ARTIST [@ZinoVinci]](https://guap.co/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Zino-4.jpg)

![Remel London’s [@Remel_London] “Mainstream” is a must attend for upcoming presenters!](https://guap.co/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/REMEL-LONDON-FLYER-FINAL-YELLOW-COMPLETE-1.png)