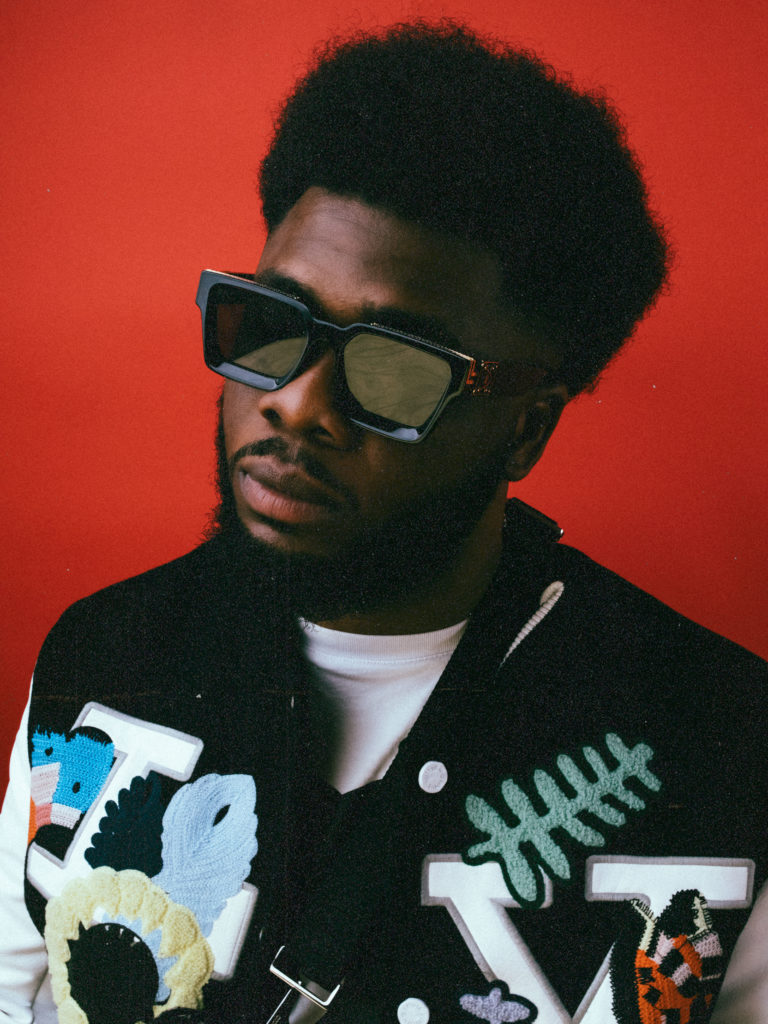

KING MAJIK & BAWSE: THE TORONTO DUO BRINGING A FRESH VOICE TO CANADA’S YOUNG AFROBEATS SCENE [@king_majik] [@bawse_fsu]

![KING MAJIK & BAWSE: THE TORONTO DUO BRINGING A FRESH VOICE TO CANADA’S YOUNG AFROBEATS SCENE [@king_majik] [@bawse_fsu]](https://guap.co/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/C6DCDA51-F7D7-4BE3-A2D7-52237819F65F-scaled-e1626878093805-180x180.jpeg)

Words by: Blossom Maduafokwa

Nigerian Afrobeats artists King Majik & Bawse talk Canadian Afrobeats Scene, migration, and their newest tape Naijanada.

Before 23-year-old Afrobeats artists King Majik and Bawse birthed their music careers in Toronto, Ontario, they first had to leave the country that they once called home.

King Majik, born Memek Inyang, spent the first 17 years of his life in the Southern Nigerian state of Akwa Ibom, leaving only to attend school in Port Harcourt, Rivers. It was only after his tenure in high school that his parents sent him to Canada in 2015 to join his siblings. On the other hand, Bawse, born Ejroghene Emedeke, was a Warri boy, attending Nigeria’s esteemed Covenant University until he received his Canadian residency in 2014 and left the country for good. Their beginnings in Canada are tinged with the classic tales of migration, the very tales that would shape the music that was to come.

The pair met at Ontario’s University of Windsor, finding companionship, out of all things, through a girl that they mutually fancied. Even before the two met, though, music was always in the cards.

“I’ve been doing music since I was eleven years old,” King Majik tells me during our interview. “Like, I would always sneak out of the house to go to the studio and my dad would be so pissed, like, “Who the heck am I?”” It was with this same passion that Majik, one day, played Bawse his music. The latter immediately went mad, insisting that Majik had a special talent that could not be ignored, and demanded that he be Majik’s manager. Out of this incident, the duo was born. In 2016 the pair made an Afrobeats track titled “Come Thru” that shook Windsor to its core, allowing them to tour throughout Ontario and creating the early groundwork for their newly blossoming careers.

“We weren’t the ‘cool guys’,” says Majik, looking back. “Nobody really expected us to have that kind of thing in our arsenal.” But of course, they did. After this drop, the pair marched on, creating melodies inspired by their biggest musical influences: Wizkid, Davido, Burna Boy, Drake, Lil Wayne, and more. They released their first project in the form of their EP The Adventures of King Majik & Bawse (2017), which featured Bashment (“Baddest Girl in Life”), Afrobeats (“Celebrate Life”), and Rap (“Level Up”). Their career quickly reached a new apex with their 2018 hit “Games”, which reached over 2 million Spotify streams and charted high on Spotify in the Netherlands.

What was more revolutionary about the two was that they were building a career off of Afrobeats in a nation with a domestic Afrobeats scene that was fledgling at best. “The community isn’t mature in Canada, so we’re really building from grassroots up. So far, the growth has been really really exponential,” King Majik says.

He makes sure not to snub pre-existing Canadian Afrobeats artists because, as the saying goes, there is nothing new under the sun. “I won’t say we’re the pioneers because people have always been trying to do Afrobeats music, like in any country,” he notes. Some essentials he hails are Canadian artists Omar, Bolu Ajibade, and Skilloj; the second having made a song with Nigerian artist Buju and the latter having released a track featuring Afrobeats crooner Peruzzi. Still, Majik did not attempt to undermine the weight of the work that he and Bawse set out to do. “I will say we really took the initiative to try to make it [Afrobeats] something bigger and something much more acceptable in the community. Because when we came, it wasn’t really a strong thing.”

This “grassroots up” mentality was part of what birthed their independent label FSU Wincity. Funnily enough, King Majik, Bawse, and their friend Eni Boy began FSU as a clothing brand, intending to use music as a tool to promote the clothes. It was only a matter of time before the music, garnering much more popularity in their community than the threads they sold, eclipsed the original mission of FSU Wincity and converted it into a record label. FSU, aside from Skilloj’s 6ixPlug Records, is one of the only Afrobeats labels in Canada, as well as a living testament to their existence as risk-takers.

“Sometimes our ideas might seem too bulky, and to be honest, unrealistic,” begins Bawse, also known as “Badman Dan”. “But that’s what we love.” To him, having an independent label gave them the freedom to explore themselves as artists, managers, and creatives. It was only with this independence that they could embark upon projects that involved huge economic gains and losses, or create supposedly “unrealistic” promotion videos that were wildly creative.

Along with being passionate, King Majik and Bawse work from a standpoint of pure logistics. Many say that Afrobeats isn’t viable in a land whose Black diaspora is largely Caribbean, but the pair think differently. “Nigeria isn’t getting better,” King Majik says, with a tinge of regret in his voice. “There are going to be way more Nigerians here in the next few years than ever.” And this is only the truth, as rising prices, unemployment, banditry, and insecurity drive many Nigerians into what they call “Japa Season”: a mad dash to escape the country, and for good. For many, all roads lead to Canada.

While tragic, this upcoming wave creates a ripe market for Canadian Afrobeats. “If we don’t tap into this from the early stages,” says Majik, “it’ll be too late later on.” Both Majik and Bawse are some of the few people willing to take risks, to spend it all, in order to create a solid Afrobeats foundation.

It was with this insistent motivation that their first studio album, Naijanda, was born.

On a fateful day in 2018, the pair linked up in Toronto to plan the future of their careers. King Majik tells me, “We came to a McDonald’s and we were like, ‘We need to do an album, we need to do something that’s gonna actually make a statement for Africans in Canada.’”

“We just came up with different crazy names,” he continues. “The first thing was ‘Canageria.’ I still have it in my notepad!” Bawse and I immediately burst into laughter. It was after a few more attempts that the pair, in all likelihood hunched over fries, burgers, and soft drinks, produced the name that would define their movement forever: Naijanada. This was to be the extra brick that would give the Canadian Afrobeats scene a firm foundation.

In deciding what they wanted the project to represent, the pair went through a number of possibilities before firmly deciding to make the album from the standpoint of people like them: born-and-bred Nigerians who had moved to Canada and were navigating the new landscape. They made an active decision to make a tape that was entirely Afrobeats. In the words of Bawse, the album, essentially, was “content from the soul.”

Released only in May, the project has charted both in Canada and Nigeria with it reaching number 46 in the official Apple Music Chart in Canada. Clearly, the pair are doing something right. “Within our community, there’s a very huge difference from before we dropped it [Naijanada] to when we did it,” King Majik tells me. “These days, when we go out, there’s way more noticeable reception that we get in the community. There’s always gonna be way more work to do, but right now, I feel like a lot has been done….and it only gets better from here.”

It definitely does. After all, the two are only planning to continue constructing the scene, helping push forward a movement with equal gravity and historical importance as the creation of Afroswing in the United Kingdom. “I feel like what our plan is right now is to build up what is in Canada right now. In the next months you’ll probably see us trying to book more shows and bring more artists out to Canada,” Majik says. A current goal of theirs is to bring over Alte singer Tems and Street artist Bella Shmurda, bringing more and more of Nigeria to the land that they now call home.

More than being just artists and producers, King Majik and Bawse are entrepreneurs, visionaries, and protectors, building the fort and simultaneously holding it down for generations to come. Certainly, it is a hefty duty: the work of spearheading the music of a new generation of Nigerians, of a new diaspora, is no easy task. However, for them – and by extension, Canadian Afrobeats – growth is not an aspiration, but destiny. It is only a matter of time before the world of Naijanada comes into full, unrestrained fruition.

![ZINO VINCI’S ‘FILTHY & DISGUSTING’EP BRINGS YOU TO THE CORE OF THE ARTIST [@ZinoVinci]](https://guap.co/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Zino-4.jpg)