“Strike MoMA, The Coalition Leading The Path To A Post-MoMA Future And Exposing A Museum’s Broken System”

The only solution to which an institution so endowed with power can be challenged is the anti-organization, Strike MoMA.

Contribution by Olisa Tasie-Amadi.

When the world was dreadfully struck by the death of George Floyd, and the rise in BlackLivesMatter protests and spread of awareness grew in the following months, countless institutions desperately raced to show support. Whether it was genuine or not, educated or not, we saw as every person, brand, group finally decided that black people and their stories sort of mattered to them, especially museums and art houses. And the Whitney Museum was one that stood out.

In an article by Jo Livingstone for The New Republic, which details a failed attempt by the Whitney Museum to support black artists in a time of sorrow, he says “The Whitney wanted to capture a moment. The artists of See In Black who found themselves newly part of this collection wanted to help fuel a movement. The artwork was the same in each case but transformed by the new context in ways Wahbeh doesn’t acknowledge. That an exhibition at one of America’s most famous art museums could be announced and then cancelled within 24 hours demonstrates just how far contemporary curatorial culture is from understanding its own role in the economy of images we all participate in.”

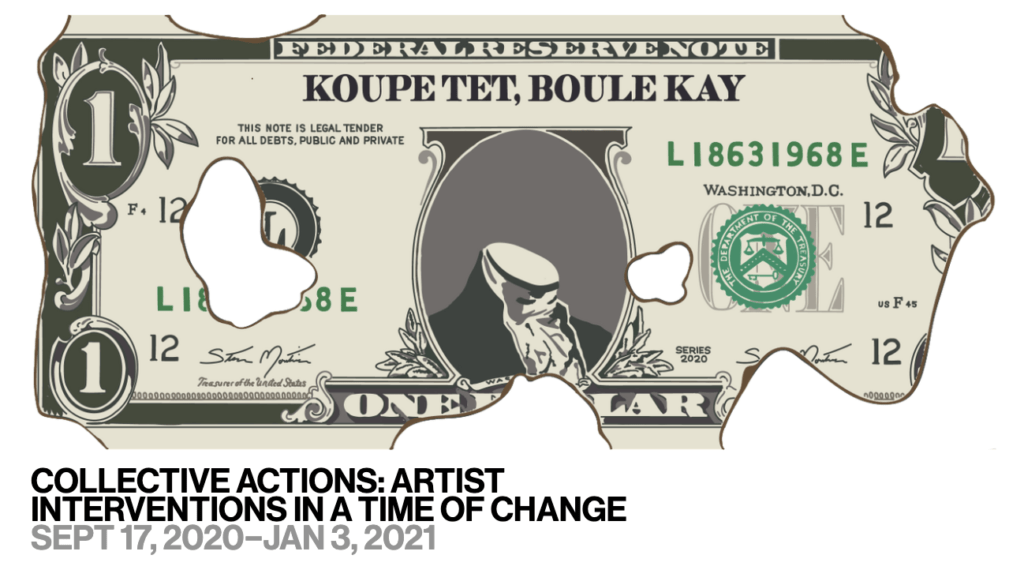

Like the Whitney, layered with inequality, elitism, and history directly linked to cultural oppression, the MoMA has served as the epicentre of the art world and how it operates. Dictating the narrative of modern art, deciding what is worthy to be considered as appropriate for the times, and creating an aesthetic that disproportionately reflects what the world looks like today. It’s fitting then, that the only solution to which an institution so endowed with power can be challenged is the anti-organization, Strike MoMA, set up right across from the museum itself.

Speaking of the dependency of MoMA and museum’s alike on donors like Leon Black — whose money openly funds wars, crimes against humanity, sex trafficking, and countless more horrors — it’s a blatant gesture of disrespect to the artists and the cultures they so desperately claim to represent and aim to include. It’s evident that the survival of the museums and the hierarchy to these elitists outweigh the need to prioritize the creators of the artworks in the museums. For Strike MoMA, the form in which these institutions take is irrelevant to the mission which is being fought for because when liberation, people, life, and land are being prioritized, the form in which it takes requires no explanation or defining.

The argument that a world with MoMA is better than a world without is an exact testament to the overt ignorance that clouds the eyes of people within the world of art because the follow-up response to that would be “For Who?” The conversation then becomes a question of humanity…being a cultured human being. That exactly is what Strike MoMA strives to highlight in its push for change amidst all the nuances that might exist.

Now in conversation with Strike MoMA organizers Amin Husain & ND on what the organization has set out to do, why it matters, and the creation of liberated spaces.

Tell me a bit about why you chose to be a part of Strike MoMA? And how did it come about?

Amin Husain: Both of us are in DecolonizeThisPlace and we’re a couple of the founding fathers of that. I think after Whitney and the summer uprising, it felt like it was important to pay attention to museums again, and cultural spaces. Learning from the successes and failures of Whitney, we studied how we can structure something differently. We spent a lot of time during the pandemic just writing thoughts down, and we organized the text which became the framework that 60 or 70 people worked on. Then we began thinking about how working groups could start doing a lot of different things with that shared politics.

ND: For me in some ways, this is like a framework for abolition and decolonization of the hierarchy that exists within MoMA. It’s not just about getting rid of one bad apple but the tree itself. We’re trying to hold these elitists, board members, and museums accountable.

Speaking on the 10-week agenda in furtherance of a Post-MoMA future, to what extent would you say the organization as a whole has achieved what it set out to do?

ND: It’s always been a process, and we don’t really work on a linear timeline of what the final plan is. I think it’s been very successful already because now people are becoming a part of the conversation, and we’re having people come out and support us, engage in our lives, expand the movement, and so much more than what we can imagine. I think the tension and the pressure on people in power is more so than ever now.

Amin Husain: I agree.

Leon Black, evidently the man at the helm of it all. Do you think removing him from any positions within the MoMA would cause any real change? What do you envision that looking like?

Amin Husain: I think our opinion is that it wouldn’t change anything, which is why our framework is set up in the sense that we wouldn’t require the institution itself to change but rather you would be bringing your own form of change to it. We also look at it in the sense that if you removed the hierarchy that exists within the museum now, they probably wouldn’t want to have the museum around anyway. That’s what we learned from the Whitney and are trying to do with MoMA. There’s a future that we have to imagine and create together in which MoMA doesn’t dictate or mediate the relationships we have with one another and the art. The goal isn’t to abolish MoMA…the goal is to leave the terms of MoMA. The art needs to be liberated, the institutions need to be held accountable, and the workers need to be in control.

ND: I think Amin did a good job of explaining my thoughts too. What we’re doing is trying to achieve a community that is built through liberated spaces — spaces not controlled by power dynamics or hierarchical institutions. In regards to what it might look like, there are certainly different shapes and forms in which it could take existence. It’s all up to the community, the artist, and the culture to define it for themselves.

“Why does the MoMA get to dictate the aesthetic for the entire world? Why do they get to define what we consider as “modern” art? That’s what we are addressing.”

Amin Hussain

Strike MoMA seems to embody less of an artistic avant-garde movement but rather an activist call for change about more social issues. What are your thoughts on this? And do you think it can also be seen as both?

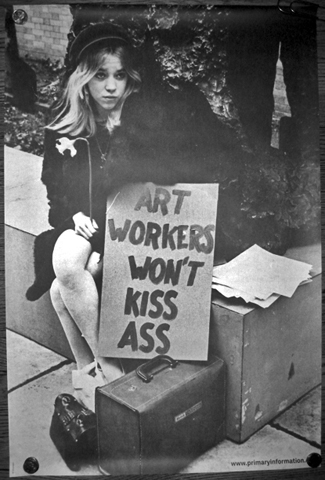

Amin Husain: It’s certainly more of a social movement, and I appreciate the question. The first point is that “avant-garde” is a very western orientation to what it means for art, and how art does things in the world. I’m trying to say that we use that phrase in a way that limits the potential and disguises the intention of why we do things. Avoiding that word removes the possibility of our movement being anchored in that western or modern perspective. What we’re doing is coming from a world that doesn’t separate art from living. So, is Strike MoMA this or that? Well…it’s neither and both. What it’s seeking to do is be in the world in a way that art needs to measure up to us and not the other way around. Institutions need to be responsible to the people and not the oligarchs.

ND: I think it’s all of these things. It’s an art movement, it’s a social movement, and it can also be a pedagogical movement. One of the things that is present in Strike MoMA is that it doesn’t differentiate between doing the research, doing the action, doing the teaching, and sort of making the aesthetics. It all depends on the place or the interest in which you join the movement from. If you come in as an artist, you look at it as an art movement. Looking at the kids in Palestine, they see that the people on the boards of these institutions are funding their wars and creating weapons of destruction, so they see it as a social movement that affects their lives. Strike MoMA tackles all of the above simultaneously because in the end they’re all connected.

Would you say the slogan and the goal of the movement, A Post-Moma Future, is used in a more ideological or structure-based sense?

Amin Husain: What we are imagining is essentially leaving…it’s the terms of exitance. And the terms of exitance for MoMA are ones in which we make irrelevant. If you look at the work we’ve done in the past, this is the first time we haven’t entered the museum — as a form of action. However, if you’re in MoMA you’re able to see the “Post-MoMA Future” across the street which is so much more appealing. We’re trying to show that the terms are not set; there isn’t one particular way to make art, and there isn’t one particular way to have the conversation. It’s literal in the sense that we shape the future now, and it’s in a physical space and also a digital space. It’s about diversifying the set of terms and perspectives that are able to communicate within a space without limits. We’re capturing moments of fleeting beauty that are also transformative in their own way.

ND: Another thing to note that is important is that these institutions are more interested in your pain than your desire. They have the tendency to shun art that even remotely touches on your desires, or what kind of place you want in this world because the moment you do that it upsets their state of quo.

Over the last few months there’s also been a huge increase in museums trying to acquire art by non-white male figures, would you say this is a result of nonstop backlash being received or do you think these acts by museums are genuine?

ND: What we’ve seen is that a lot of institutions are not getting funding if they don’t have diversity, equity, and inclusion in their agenda. It’s more than just caring for them because it’s become an economic problem right now. For museums, I think now they start to see that there is now a huge market for art that is not white. It’s genuine in a different sense for them. MoMA especially is racing to stamp themselves as the museum with the most diverse art or the most diverse staff. In the end, it doesn’t change what these institutions really stand for.

Amin Husain: Is it opportunistic? Is it part of the colonialistic project to take away the energy or the radicality of the movement now? Well…I think it’s a lot of things. I think there are totally well-meaning people like artists and curators who genuinely want to create art and spaces that have meaning. I think there are two ways to look at it. Artists of non-white backgrounds are being sought after to be part of these new exhibitions, and on one level it’s a good thing, and on another level, it’s not the horizon because it dampens the real struggle. If you can’t talk about how little people get paid, how bad people get treated, how bad the people that own the art are, then what does it mean to be included in that system? You’re really only legitimizing it.

Beyond curators, museum enthusiasts, and the many activists that stand with the coalition, who else do you think has a duty or should also be engaging in the conversation? How do you think they can do so best?

Amin Husain: I think that in the terms of the framework of struggle, we outline what we think is the kind of liberatory politics that we can all have with each other. You can make demands, you can make art, you can do all things, and all of this is really just individual choice in autonomy. I think what’s important is the recognition that our liberation requires us all, and we’re in different positions, have different experiences, and are in different modes of oppression. And we also, here in New York, have a responsibility to the world because there is no bigger definer or dictator of art and aesthetics than the MoMA. There is no other place that has who’s who of assholes…money that goes way way back that is directly linked to colonizers. Then within each of us, we have to say how does that relate to our art, our living, our practice, and how can I use my intellectual prowess and sort of maneuver around it or contradict its flow. We’re trying to exclude MoMA from the conversations we should be having with each other, and we can have it through the art we make or the conversations we initiate.

We’ve also witnessed the tragedies that continue to plague the people of Palestine, and the support from Strike MoMA is more evident than ever towards them. Would you say you stand for something more than just advocating for change within the world of art?

Amin Husain: Strike MoMA is definitely specific but in a way, it’s also a metaphor. It’s about striking modernity in spite of the struggle, and modes of resisting and building in the 21st century that isn’t nation-state-centric. And our experience has been involved in working around social movements, and then have moved into working in the cultural arena. Movements take years to develop and solidify, and revolutionary consciousness takes generations you know? So, looking at the work we have done in the past, I would say the most mature effort we have done and been a part of is Strike MoMA. I guess…what we plan to do with or alongside Strike MoMA is yet to be seen.

ND: I think we don’t know where Strike MoMA goes as of now. We’re also focusing on building relationships because that’s what this work is about, and how the work is able to further itself.

To support Strike MoMA and keep up with their work, visit their website here.

Contribution by Olisa Tasie-Amadi.

Check out the GUAP Arts & Culture section, to discover new art, film, and creative individuals.

![ZINO VINCI’S ‘FILTHY & DISGUSTING’EP BRINGS YOU TO THE CORE OF THE ARTIST [@ZinoVinci]](https://guap.co/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Zino-4.jpg)

![Remel London’s [@Remel_London] “Mainstream” is a must attend for upcoming presenters!](https://guap.co/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/REMEL-LONDON-FLYER-FINAL-YELLOW-COMPLETE-1.png)