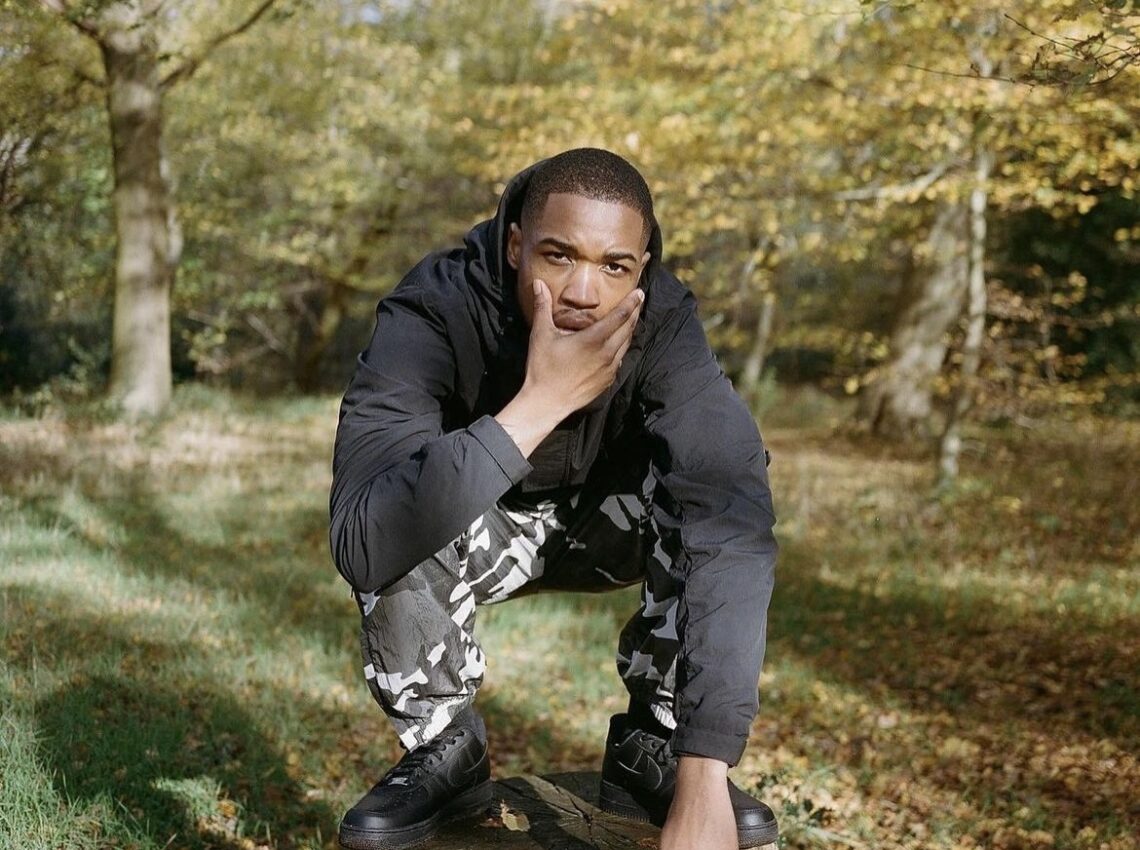

MUSIC IN BLACK CINEMA: A SPIKE LEE STORY [@OFFICIALSPIKELEE]

![MUSIC IN BLACK CINEMA: A SPIKE LEE STORY [@OFFICIALSPIKELEE]](https://guap.co/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/27A26C93-550F-4DD4-B3DB-DF3FE54C2493-1140x850.jpeg)

A brief 101 on the brilliance of Spike Lee’s transformative soundtracks…

“I start thinking about the music for my films at the same moment I’m writing the script… It’s part of my creative process. I pay as much attention to the music as I do to the acting, cinematography, editing, production design, costume design, and casting.” – Spike Lee

Great movies and great soundtracks go hand in hand; sometimes soundtracks transcend the movie itself. How many of us have never seen The Bodyguard but can still belt out ‘I Will Always Love You’ at an opportune moment? Sound is essential to cinema, but what do these things mean in the context of blackness? In a landscape where some of the most prolific narratives around black achievement involve the entertainment industry (see music, sports, movies, etc.), who shapes the eyes through which we see? Moreover, how do they shape them and for what purpose?

For this exploration, unfortunately, we have to simplify. To truly delve into the richness of the subject requires a format far larger than this article allows. Instead, we’re going to look at an influential pocket of black cinema — the creations of Spike Lee. Thankfully, the Brooklyn Museum is in the midst of an exhibition entirely around his creative influences, so we were able to get an in-depth look at this process in the same place that birthed his creativity. We learned many things, specifically how he exercised two crucial elements that set a course and defined a direction for a formative part of black American cinema. These elements are creation and reclamation.

“Creation” is a powerful word, holding with it a well of responsibility and history. One of the most common uses of music in Spike Lee’s films is celebration. Communally seeking respite through the hope these shared experiences bring them, from the opening sequence of Do the Right Thing to the dance scene with Ru Paul in Crooklyn, his characters always endure. They find moments of joy through music and dance. Spike Lee’s father was a jazz musician, so it’s not hard to draw that line. The final scenes of Mo’ Better Blues are set to John Coltrane’s ‘A Love Supreme. Pt.1-Acknowledgement’ are a deeply touching example of the beauty Spike Lee encapsulates and how he uses his own connections to inform his work.

Maybe one of his strongest and most influential visions in creating music came from the soundtrack to Do the Right Thing. He had a specific vision and asked Public Enemy to write the soundtrack. What they came back with became one of the cornerstones for the proliferation of Hip Hop as we know it today, holding number 2 on Rolling Stone’s 500 Greatest Songs of All Time list. ‘Fight the Power’ was an interpolation of the eponymous 1975 Isley Brothers song, a rallying cry against police brutality and discrimination.

“Reclamation” is a common subject in the discussion around racialized narratives and black liberation. Though more often brought up in conversations to do with language and vernacular, it is just as effectively applied to sound. The premise kind of goes ‘We make our own, and we’ll do yours one better.’ The soundtrack to the 2018 film BlacKkKlansman is a striking example of this. It made the rounds at its respective award season, winning multiple Oscars, including for its original score composed by long-time Spike Lee collaborator Terence Blanchard.

For those unfamiliar, the movie is set in the 70s and sees a black detective infiltrate the KKK, drawing parallels between race relations in the 70s and the modern-day. The soundtrack exercises reclamation in a myriad of ways. For a full scope, it’s worth watching this fascinating breakdown by Jazz Night In America. The title of one of the most commonly recurring songs through BlacKkKlansman is ‘Blut Und Boden (Blood and Soil).’ Terence is most well known for his trumpet playing, so the choice to focus on the guitar for this theme was a conscious one, influenced heavily by Parliament-Funkadelic and even more so by Jimi Hendrix’s performance of ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’ at Woodstock 1969. One of the most iconic performances in Rock history, intended to protest the U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War and its treatment of black veterans, a subject Spike Lee delved into more deeply in his 2020 film Da 5 Bloods (accompanied again by a stellar soundtrack, this time woven with a selection of Marvin Gaye tracks). The practice of reclaiming sound and championing counterculture is not just a great way to create movie soundtracks; it’s also a long-running tradition in so many civil rights movements.

The world is no stranger to the fact that the narratives we consume shape our perceptions. There are few places where our perceptions are more malleable than the cinema. In front of the big screen or at home on the sofa, our spheres of existence become moulded by the people who tell our stories. It’s a wonderful thing to have that placed in the hands of an individual like Spike Lee. A master in what it means to express music through visual media, who sees all the beauty, depth, and complexity of our experiences and is committed to doing them justice.

Discover More from GUAP’s Music Section here.

![ZINO VINCI’S ‘FILTHY & DISGUSTING’EP BRINGS YOU TO THE CORE OF THE ARTIST [@ZinoVinci]](https://guap.co/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Zino-4.jpg)