An eclectic journey of memory and music – Nadeem Din-Gabisi shares his latest release ‘Pool’

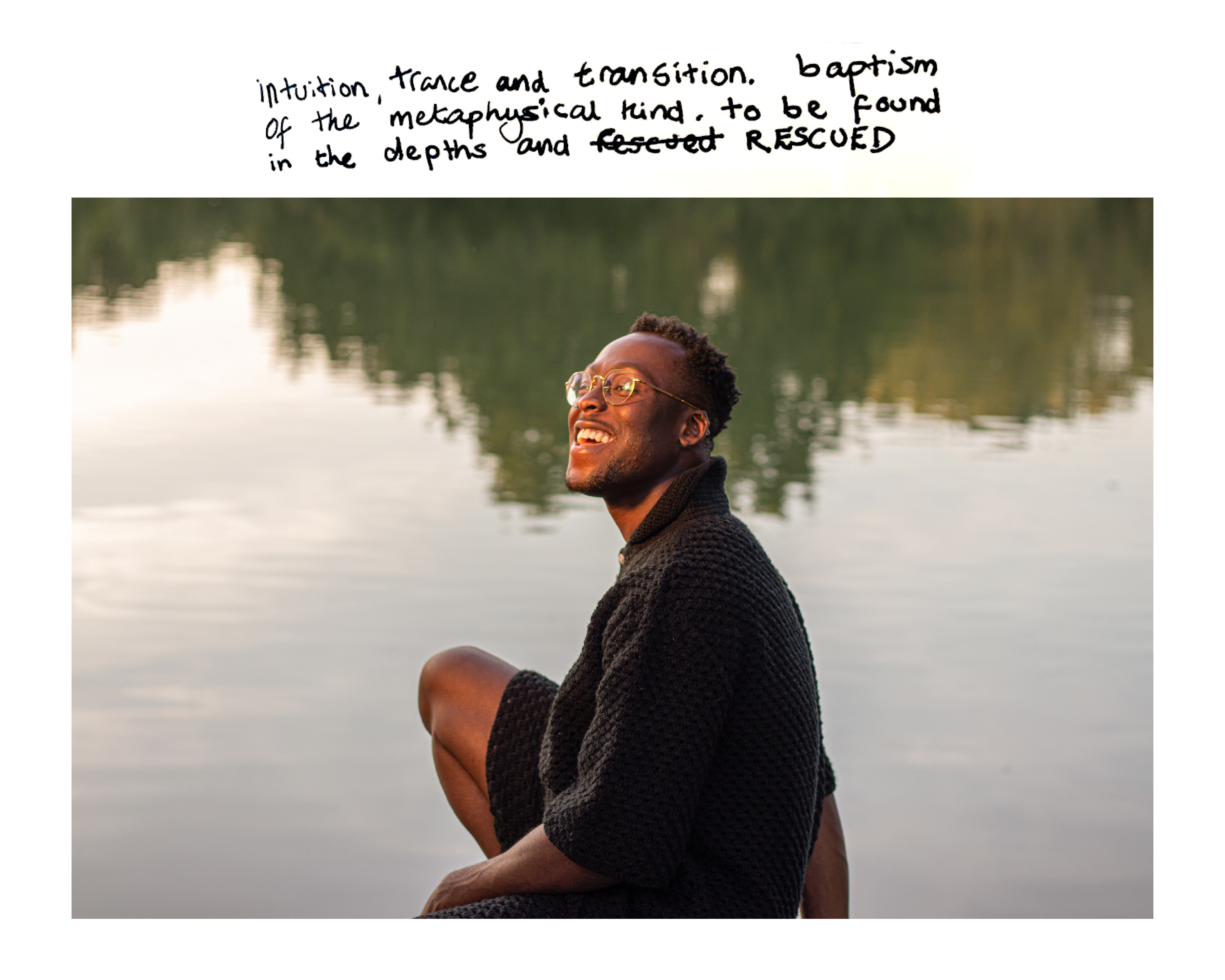

Combining hip-hop, jazz, and Afrobeat rhythms, POOL excavates into Nadeem’s childhood and takes us through a poetic, eclectic and introspective narration, questioning themes such as belonging, vulnerability, and faith. Soothing images of water as a saving force are juxtaposed by references to water as a subversive power. Exits are also entrances, the line between the shallow end and the deep one is blurrier than we might think.

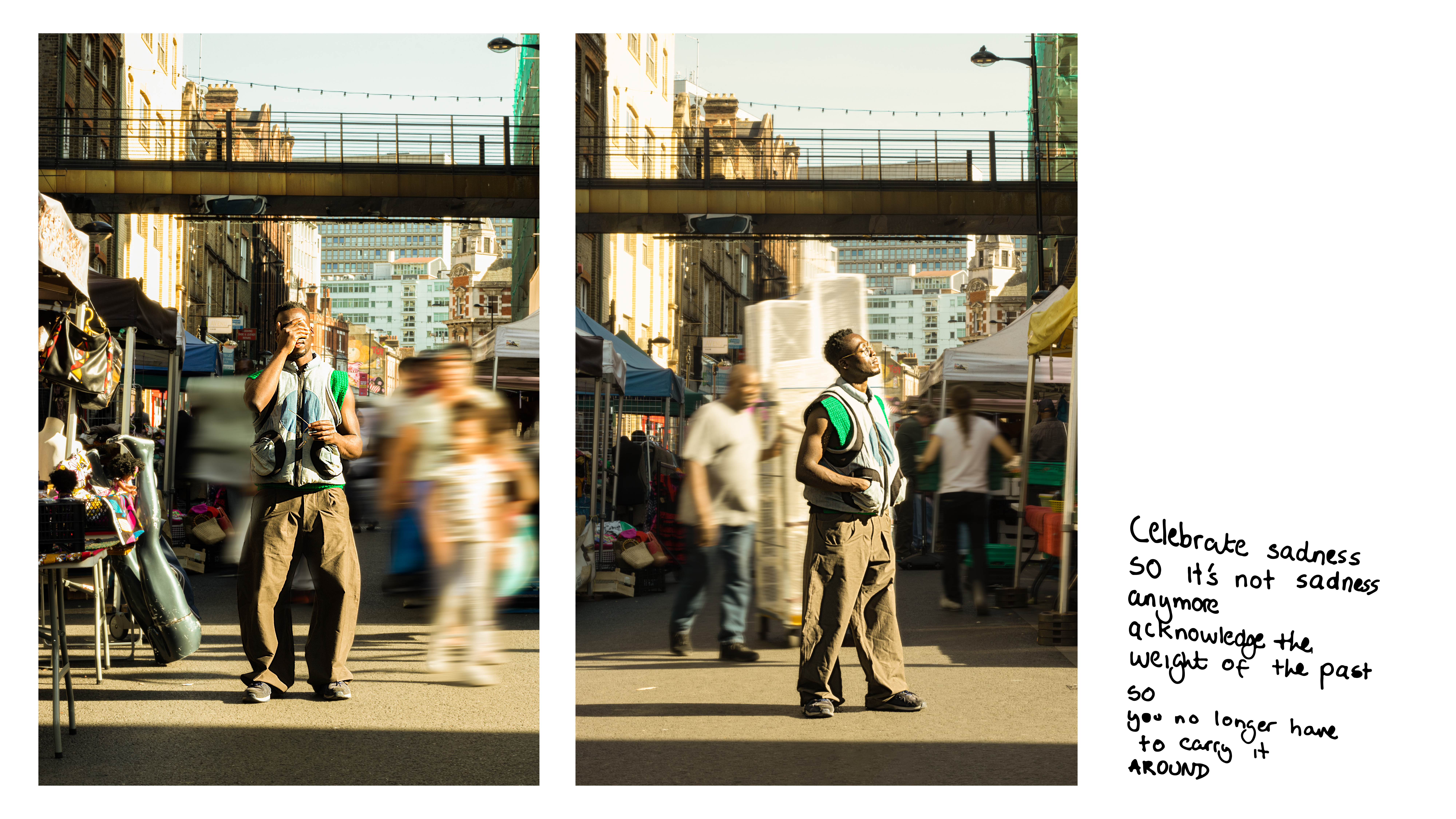

Shortly after the release of the album, I asked Nadeem to guide me through the spaces that were crucial to his personal and artistic development, the places that were determined during the conception and making of the album. The photographs were taken in the neighborhoods of Croydon and Norwood, where Nadeem spent his childhood and where his fascination with water developed.

Approached with a documentary lens, the photographs investigate Nadeem’s relationship with the spaces of his early memories, looking back at how those environments shaped his growth and perception. The images are complemented by lyrics from the album, notes, and reflections from Nadeem’s personal archives.

Nadeem’s history is furtherly enhanced by clothes designed by Mapalo Ndhlovu (London-based fashion designer, and founder of Studio Mapalo). Mapalo’s designs are created to tell the visual narrative of how his childhood in Zambia and living in Yorkshire and London have collided. He integrates African style into western culture, providing an insight into how cultures could be visually combined. Assistance with lights, locations, and general organization was provided by Ant Belle, one of the most knowledgeable emerging creatives working in the camera department.

Could you tell me a bit about yourself and your latest musical project?

I am a British Born African of Sierra Leonean descent. That description is important, as the histories and currents of all of those places inform me as a person and the work that I produce. My first full-length musical offering, POOL, is the beginning of an exploration of these complex places and identities through a musical lens. I see myself as a storyteller using whatever medium is necessary to explore my inner and outer worlds. POOL is an examination of moments of trauma and happiness in childhood. I use those moments as a diving board to explore the mental health issues and coping mechanisms of many young black men, born in inner and outer London. The album questions and attempts to answer why some of these men swim, why some sink, and why some others don’t enter the POOL.

How did you first start to associate London with a pool?

Well, it’s not just London that is a pool, it’s any place that people find themselves in. What’s specific to London is the strength needed to thrive in the city, to not drown. I don’t think it’s necessarily a good thing that one needs so much resilience to live and not necessarily have a good quality of life, with air quality space, food, etc.

Living shouldn’t be that hard. Having moved out of London recently I’ve begun to see that this isn’t necessarily a London-centric thing. Perhaps the world has always been a pool and that’s why people and other animals move and migrate to find the most suitable places for themselves. What I talk about in the album, in regards to Lon- don’s pool-like quality is a reflection of the current moment we are living in where the majority of people worldwide have armbands and floats and very few are able to swim completely freely.

You talk about the push and pull of belonging: how does living in a city like London influence this?

The push and pull of belonging I mention is primarily related to me being a second-generation immigrant of Sierra Leonean, Krio descent with parents and family attached to another land than the one I know.

As someone born in the land your parents have come to for betterment, one has to develop a different consciousness, as you house multiplicities of belonging and ideas of home as a default. The home your parents refer to might not be your home but because of how they feel towards space you may long for that home, want nothing to do with it, or something in between. I’m realising that belonging is not so much an external thing but an internal one that is helped or hindered by the space one finds themselves in.

What areas of the city are shallow and safe, and which ones are deeper?

Well, the shallow end isn’t always safe, it can actually be more dangerous than the deep end because you think you are safe. If you aren’t moving and aren’t growing but you have the ability to, then the shallow end becomes a dangerous place. I think any place and not just London, any place that forces you to grow and allows you the room and opportunities to build and prosper is a safe place. London is becoming less and less safe in that regard. The cost of rent and living moves a lot of people to either hold on, stagnate or move out. It seems that there’s very little middle ground, or middle water to continue the metaphor. London has been becoming, for a long time, a playground for the rich. With housing built for them and no one else, leaving the vast majority of people unable to take natural steps of progression.

I suppose these issues will really come to a head when there is no new influx of people coming to these cities. When the reality is so far from the dream that we create our own realities in new spaces and keep it quiet so the rent doesn’t go up!

How have the places you grew up in impacted you?

I actually wanted to say something about the suburbs and the suburban experience. Having grown up in these spaces, being out of the center pushed me towards digging and searching not just in the realms of music but of self-definition. My boredom and yearning were given the time to find a resting place. Whether I rested there or not was dependent on how I was feeling but when I did I always found something worth keeping Growing up I didn’t really think about the limitations or expansiveness of the place I was in.

I spent more time in my head than in the world, and when I did think about my space I just didn’t have enough experiences in it to form clear feelings. I suppose it wasn’t until maybe sixteen or so that I began to think about my place in a very physical sense. I was frustrated and still am (but now have a way to channel these frustrations) by the hold hyper-capitalism has on our growth and movement in Norwood, Croydon, and this country as a whole really.

I used to think these frustrations were specific to certain localities but the lack of certain infrastructure, affordable housing, access to green spaces, etc. All these things affect most people who don’t have a certain level of wealth. It perhaps affects more viscerally black and brown people and working-class English people. I don’t think anyone is immune, it’s just that some people have better buffers and are more used to the pervasive inequality that exists.

With that said, despite all of these infractions on spirit the people in these spaces through diligence and defiance work towards making these environments liveable and lovable, rising above hindrance and hardship to create beauty. When I do think about space and spaces as a young person I think often about spaces families gathered in houses, halls, and churches. The actual city or town or suburb was less of a thing. It was more so the people gathered in the spaces and their transformation of them even if it was momentary that sticks with me.

–

This was a collaboration between the Originals Creator Network programme

Photos and interview by Elisa Mazzuca

Styling by Mapalo Ndlovhu

Lighting by Ant Belle

![ZINO VINCI’S ‘FILTHY & DISGUSTING’EP BRINGS YOU TO THE CORE OF THE ARTIST [@ZinoVinci]](https://guap.co/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Zino-4.jpg)